Unboxing BusyBox – 14 new vulnerabilities uncovered by Claroty and JFrog

Background

Embedded devices with limited memory and storage resources are likely to leverage a tool such as BusyBox, which is marketed as the Swiss Army Knife of embedded Linux. BusyBox is a software suite of many useful Unix utilities, known as applets, that are packaged as a single executable file. Within BusyBox you can find a full-fledged shell, a DHCP client/server, and small utilities such as cp, ls, grep, and others. You’re likely to find many OT and IoT devices running BusyBox, including popular programmable logic controllers (PLCs), human-machine interfaces (HMIs), and remote terminal units (RTUs)—many of which now run on Linux.

As part of our commitment to improving open-source software security, Claroty’s Team82 and JFrog collaborated on a vulnerability research project examining BusyBox. Using static and dynamic techniques, Claroty’s Team82 and JFrog discovered 14 vulnerabilities affecting the latest version of BusyBox. All vulnerabilities were privately disclosed and fixed by BusyBox in version 1.34.0, which was released Aug. 19.

In most cases, the expected impact of these issues is denial of service (DoS). However, in rarer cases, these issues can also lead to information leaks and possibly remote code execution.

In this report, we provide details on the vulnerabilities we discovered, elaborate on who is affected, discuss our research methodology, explain one of the vulnerabilities in depth, and suggest fixes and workarounds for these issues.

In addition to disclosing the vulnerabilities, Team82 is also open-sourcing our custom AFL fuzzing harnesses, which were responsible for triggering many of the mentioned vulnerabilities. Hopefully this will help fellow researchers find and disclose more issues.

The Vulnerabilities

| CVE ID | Description | Affected applet | Affected versions (inclusive) | Impact | CVSS v3.1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2021-42373 | A NULL pointer dereference in man leads to denial of service when a section name is supplied but no page argument is given |

man |

1.33.0-1.33.1 | DoS | 5.1 |

| CVE-2021-42374 | An out-of-bounds heap read in unlzma leads to information leak and denial of service when crafted LZMA-compressed input is decompressed. This can be triggered by any applet/format that internally supports LZMA compression. |

lzma/unlzma and more (see below) |

1.27.0 – 1.33.1 | DoS & InfoLeak | 6.5 |

| CVE-2021-42375 | An incorrect handling of a special element in ash leads to denial of service when processing a crafted shell command, due to the shell mistaking specific characters for reserved characters. This may be used for DoS under rare conditions of filtered command input. |

ash |

1.33.1 | DoS | 4.1 |

| CVE-2021-42376 | A NULL pointer dereference in hush leads to denial of service when processing a crafted shell command, due to missing validation after a \x03 delimiter character. This may be used for DoS under very rare conditions of filtered command input. |

hush |

1.16-1.31.1 | DoS | 4.1 |

| CVE-2021-42377 | An attacker-controlled pointer free in hush leads to denial of service and possible code execution when processing a crafted shell command, due to the shell mishandling the &&& string. This may be used for remote code execution under rare conditions of filtered command input. |

hush |

1.33.0-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.4 |

| CVE-2021-42378 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the getvar_i function |

awk |

1.16-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42379 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the next_input_file function |

awk |

1.18-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42380 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the clrvar function |

awk |

1.28-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42381 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the hash_init function |

awk |

1.21-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42382 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the getvar_s function |

awk |

1.26-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42383 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the evaluate function |

awk |

1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42384 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the handle_special function |

awk |

1.18-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42385 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the evaluate function |

awk |

1.16-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

| CVE-2021-42386 | A use-after-free in awk leads to denial of service and possibly code execution when processing a crafted awk pattern in the nvalloc function |

awk |

1.16-1.33.1 | DoS & Possible RCE | 6.6 |

Triggering the Vulnerabilities

Since the affected applets are not daemons, each vulnerability can only be exploited if the vulnerable applet is fed with untrusted data (usually through a command-line argument). Specifically, these are the conditions that must occur for each vulnerability to be triggered:

CVE-2021-42373 – Applies if the attacker can control all parameters passed to man.

man is built by the default BusyBox configuration, but not shipped with Ubuntu’s default BusyBox binary.

CVE-2021-42374 – Applies if the attacker can supply a crafted compressed file, that will be decompressed by using unlzma.

Note that even if the unlzma applet is not available, but CONFIG_FEATURE_SEAMLESS_LZMA (enabled by default) is enabled, other applets such as tar, unzip, rpm, dpkg,lzma and man can also reach the vulnerable code when handling a file with the .lzma filename suffix.

unlzma is built by the default BusyBox configuration and shipped with Ubuntu’s default BusyBox binary.

CVE-2021-42375 – Applies if the attacker can supply a command line to ash that contains the special characters $, {, }, # .

ash is built by the default BusyBox configuration and shipped with Ubuntu’s default BusyBox binary.

CVE-2021-42376 – Applies if the attacker can supply a command line to hush that contains the special character \x03 (delimiter).

hush is built by the default BusyBox configuration but not shipped with Ubuntu’s default BusyBox binary.

CVE-2021-42377 – Applies if the attacker can supply a command line to hush that contains the special character &.

CVE-2021-42378 – CVE-2021-42386 – Applies if the attacker can supply an arbitrary pattern to awk (the pattern is the first positional argument this applet takes).

awkƒ is built by the default BusyBox configuration and shipped with Ubuntu’s default BusyBox binary.

Research Methodology

To research BusyBox, we used static and dynamic analysis approaches.

First, a manual review of the BusyBox source code was conducted in a top-down approach (following user input up to specific applet handling). We also looked for obvious logical/memory corruption vulnerabilities.

The next approach was fuzzing. We compiled BusyBox with ASan and implemented an AFL harness for each BusyBox applet. Each harness was subsequently optimized by removing unnecessary parts of the code, running multiple fuzzing cycles on the same process (persistent mode), and running multiple fuzzed instances in parallel.

We started from fuzzing all the daemon applets, including HTTP, Telnet, DNS, DHCP, NTP and others. Many code changes were required in order to effectively fuzz network-based input. For example, the main modification we performed was to replace all recv functions with input from STDIN in order to support fuzzed inputs. Similar changes were done when we fuzzed non-server applets as well.

We prepared a couple of examples for each applet and ran hundreds of fuzzed BusyBox instances for a few days. This gave us tens of thousands of crashes to evaluate. We had to create classes of crashes with the same root cause to help reduce the volume of crashes we had in our sample set. Later, we minimized each group representative in order to work with a small subset of unique crash inputs.

To fulfill these tasks, we developed automatic tooling that digested all crash data and classified it based on the crash analysis report which mainly includes the crash stack trace, registers, and assembly code of the relevant code area. For example, we merged cases with similar crash stack traces because they usually had the same problematic root cause.

Finally, we researched each unique crash and minimized its input vector in order to understand the root cause, which allowed us to create a proof-of-concept (PoC) that exploits the vulnerability responsible for the crash. In addition, we tested our PoCs against several BusyBox versions to understand when the bugs were introduced to the source code.

In summary, following are the steps we took in our research:

- Code review

- Fuzzing

- Reduction & Minimization

- Triage

- PoC

- Testing multiple versions

- Disclosure

Guide and Resources for BusyBox Fuzzing

As part of our commitment to the open source security and security communities, we created a simple on-boarding guide detailing how to fuzz BusyBox. The guide is published alongside all of the fuzzing harnesses we wrote as part of our fuzzing efforts. We hope these fuzzing harnesses can be further improved by the community, in order to find and fix even more bugs in BusyBox.

All materials are available on Claroty’s GitHub page.

Threat Analysis

To assess the threat level posed by these vulnerabilities, we inspected JFrog’s database of more than 10,000 embedded firmware images (composed of only publicly available firmware images, and not ones uploaded to JFrog Artifactory). We found that 40% of them contained a BusyBox executable file that is linked with one of the affected applets, making these issues extremely widespread among Linux-based embedded firmware.

However, we believe these issues do not currently pose a critical security threat because:

- The DoS vulnerabilities are trivial to exploit, but the impact is usually mitigated by the fact that applets almost always run as a separate forked process.

- The information leak vulnerability is nontrivial to exploit (see, next section).

- The use-after-free vulnerabilities may be exploitable for remote code execution, but currently we did not attempt to create a weaponized exploit for them. In addition, it is quite rare (and inherently unsafe) to process an

awkpattern from external input.

Deep Dive on CVE-2021-42374 – LZMA OOB Read

Lempel–Ziv–Markov Chain Algorithm (LZMA) and Range Coding

LZMA is a compression algorithm that uses dictionary compression, and encodes its output using a range encoder. The dictionary compressor finds matches using sophisticated dictionary data structures, and produces a stream of literal symbols and phrase references, which are encoded one bit at a time by the range encoder, using a complex model to make a probability prediction of each bit.

The compression algorithm encodes the compressed stream as a stream of bits using an adaptive binary range coder. Data is broken into packets, where each packet describes either a single byte, or an LZ77 sequence, with its length and distance implicitly or explicitly encoded.

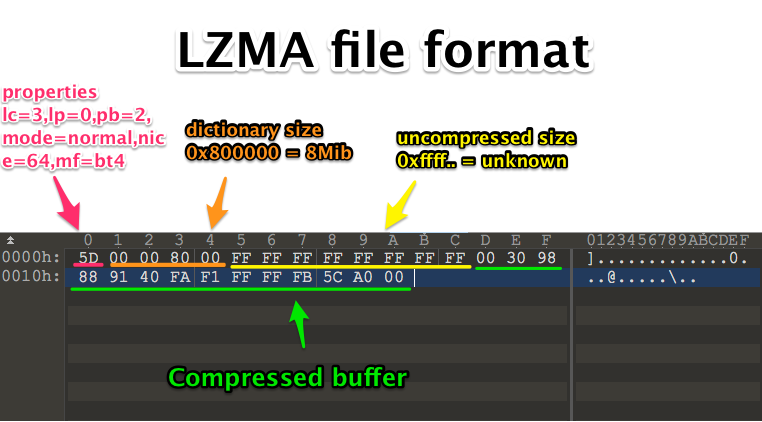

The .lzma format consists of a 13-byte header followed by the LZMA compressed data. Here is a small example of compressing the string “abc” using:

In order to output the decompressed stream, LZMA implementations use a memory buffer that is initialized in the size of the user-provided dictionary size (part of the LZMA header). Once that buffer is filled, it automatically outputs the data thus far, flushes the buffer and starts filling it up again.

The Vulnerability

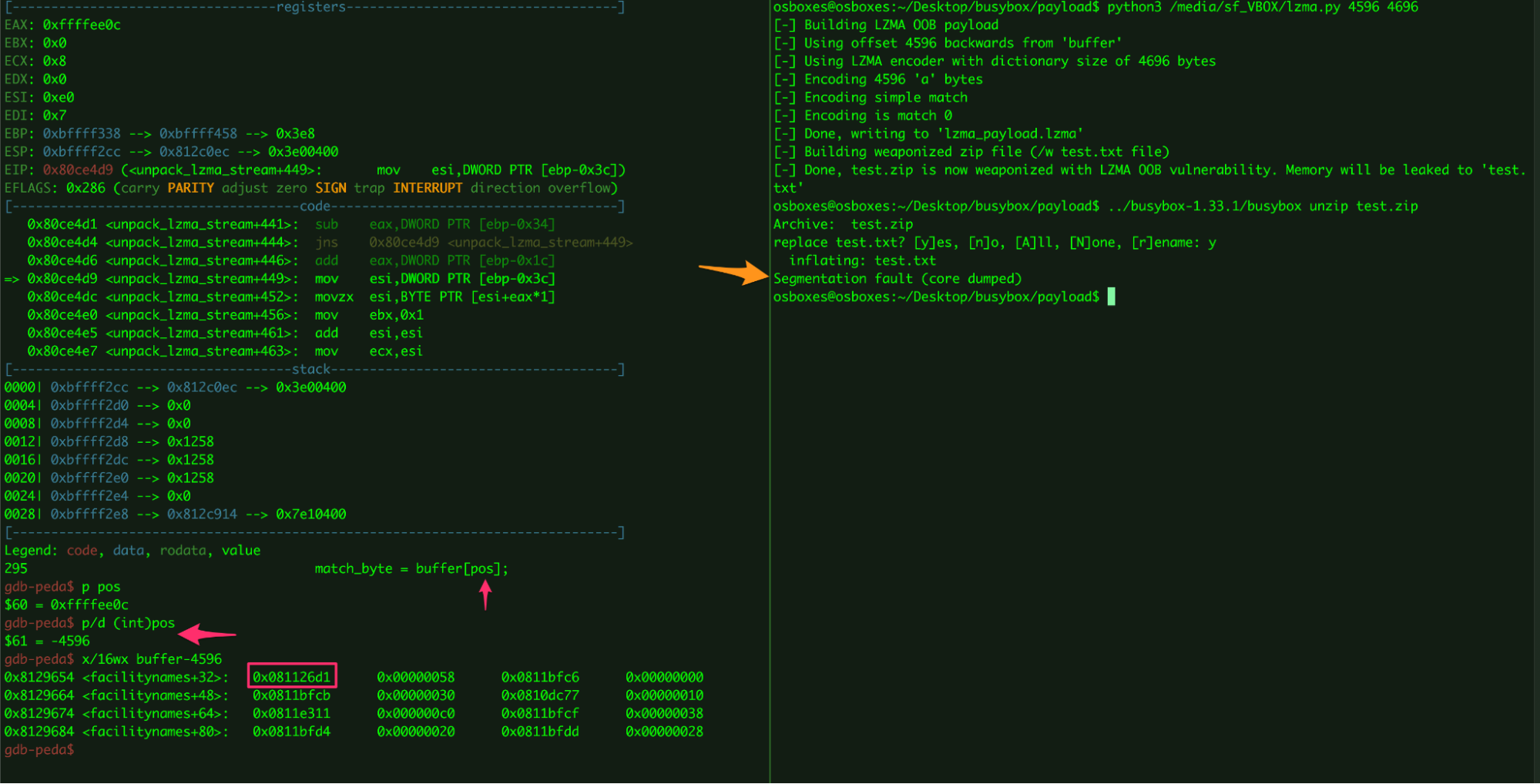

The vulnerability is caused by an insufficient size check in the unpack_lzma_stream function (in decompress_unlzma.c) when the state >= LZMA_NUM_LIT_STATES:

while (global_pos + buffer_pos < header.dst_size) {

...

uint32_t pos;

pos = buffer_pos - rep0;

if ((int32_t)pos < 0) // Insufficient check

pos += header.dict_size; // dict_size is user-controlled

match_byte = buffer[pos]; // Read OOB may occur here

do {

int bit;

match_byte <<= 1;

bit = match_byte & 0x100;

...To trigger the vulnerability and to control the starting offset where we will leak data from, we need to make sure that the following conditions are satisfied:

buffer_pos = 0

and

rep0 = offset + dict_size

This way, pos will be equal to -(offset + dict_size). After adding dict_size, pos will be -offset and so we could leak memory from our desired offset through match_byte. The leaked memory will most likely contain pointers which could further assist attackers in their exploitation campaign (ex. by facilitating ASLR bypass).

Causing an Out-of-Bounds Access

The general idea to exploit this vulnerability is to prepare a specifically crafted LZMA encoded stream, so that when it is decoded, both conditions will be filled and pos will be equal to a negative number -offset. Eventually, the decompressed stream will contain the leaked memory, which will be written to the output steam.

To satisfy the first condition buffer_pos = 0, we need to make sure our code flow (state >= LZMA_NUM_LIT_STATES) is reached right after the current decompressed buffer stream is flushed and so the buffer pointer position will be 0. We can achieve this by reaching the last iteration of a current match:

buffer[buffer_pos++] = previous_byte;

if (buffer_pos == header.dict_size) {

buffer_pos = 0;

global_pos += header.dict_size;

if (transformer_write(xstate, buffer, header.dict_size) != (ssize_t)header.dict_size)

goto bad;

IF_DESKTOP(total_written += header.dict_size;)

}

len--;

} while (len != 0 && buffer_pos < header.dst_size); // match_last_iteration will end with buffer_pos = 0;The second condition is more difficult to satisfy and requires intimate knowledge of how the LZMA algorithm works. The general idea is to encode a special length in the LZMA bit stream so that when decoded it will be used by the rep0 variable.

To conclude, in order to reach an OOB condition, we need to write some bytes, then use a match to fill the buffer to header.dict_size and change rep0 to our desired value. Therefore, pos will be equal -offset and we could leak bytes from offset as a reference to the buffer pointer.

Leaking Bits from Out-of-Bounds Memory

After reading the match_byte, we will get to this flow:

do {

int bit;

match_byte <<= 1;

bit = match_byte & 0x100;

bit ^= (rc_get_bit(rc, prob + 0x100 + bit + mi, &mi) << 8); /* 0x100 or 0 */

if (bit)

break;

} while (mi < 0x100);

while (mi < 0x100) {

rc_get_bit(rc, prob + mi, &mi);

}As long as the bits match our match_byte (the leaked byte), it will be in the loop that reads the probability from prob + 0x100 + bit + mi, but once one bit is not matched, it reads it from prob + mi. We can detect what was the first unmatched bit, by checking if prob + mi was changed by writing more literal bytes, or if the probability was changed and we got a different output. Finally, the leaked bits will get flushed to the decompressed buffer.

Weaponizing ZIP Files

Although the vulnerability was found in the LZMA decompression algorithm, we found that many applets support an LZMA compression and will try to decompress encoded LZMA streams by default (see section, “Fixes and Workarounds” for the configuration flags governing this behavior). For example, the ubiquitous ZIP format supports LZMA compression as a “type 14” compression.

From an attacker’s perspective, ZIP is a much better attack vector since:

unzipinvocations are much more common than direct invocations ofunlzma.- With this attack vector, there are no constraints on the filename that’s going to be unzipped (unlike in the tar attack vector, which requires a

.lzmasuffix). - The leaked data can be extracted and saved into files that can be later read remotely. For example, this can happen in an embedded web service that permits uploading zip files with media resources, which will get extracted to an accessible location. From there, the attacker could read the leaked memory data.

To test this, we built a small PoC script that generates a weaponized ZIP where one of the files is compressed using LZMA:

Fixes and Workarounds

All 14 vulnerabilities have been fixed in BusyBox 1.34.0 (direct download link) and users are urged to upgrade.

If upgrading BusyBox is not possible (due to specific version compatibility needs), BusyBox 1.33.1 and earlier versions can be compiled without the vulnerable functionality (applets) as a workaround.

After running make defconfig in BusyBox’s source directory (or if reusing a previous configuration), edit the .config file as such:

man– Comment outCONFIG_MAN=ylzma– Comment outCONFIG_UNLZMA=y,CONFIG_FEATURE_SEAMLESS_LZMA=yandCONFIG_FEATURE_UNZIP_LZMA=yash– Comment outCONFIG_ASH=yhush– Comment outCONFIG_HUSH=yawk– Comment outCONFIG_AWK=y

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Denys Vlasenko from BusyBox’s development team for validating and fixing all of the above issues in a swift manner for version 1.34.0.