Vulnerability or Not a Vulnerability?

Disputed CVEs: It’s Not a Bug, It’s a Debate

Every CVE starts as a vulnerability claim, but not every claim ends in agreement. Between researchers racing to disclose vulnerabilities, and open-source maintainers guarding the stability and reputation of their projects, a gray zone appears where “vulnerability” becomes a matter of debate.

This is the story of many disputed CVEs. Where “vulnerability” is rarely a yes-or-no answer. Should maintainers be expected to fix and secure every conceivable edge case in their projects, or is there a point where responsibility shifts to developers to use open-source code safely and as intended?

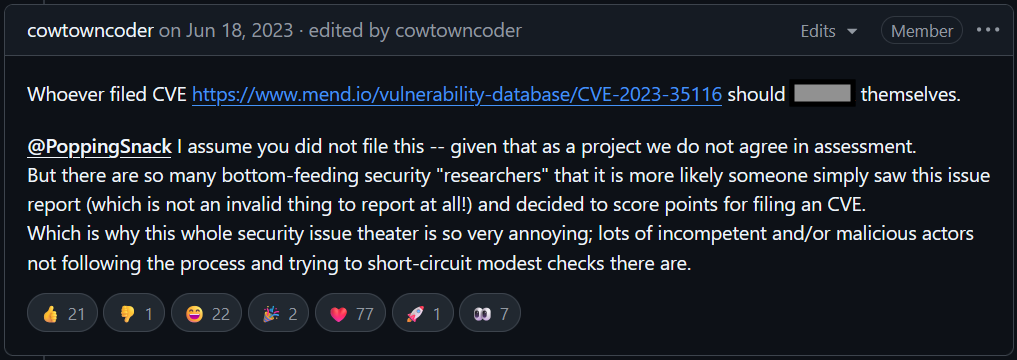

Years of dealing with low-quality reports and misaligned CVEs can leave maintainers primed to respond with anger rather than explanation:

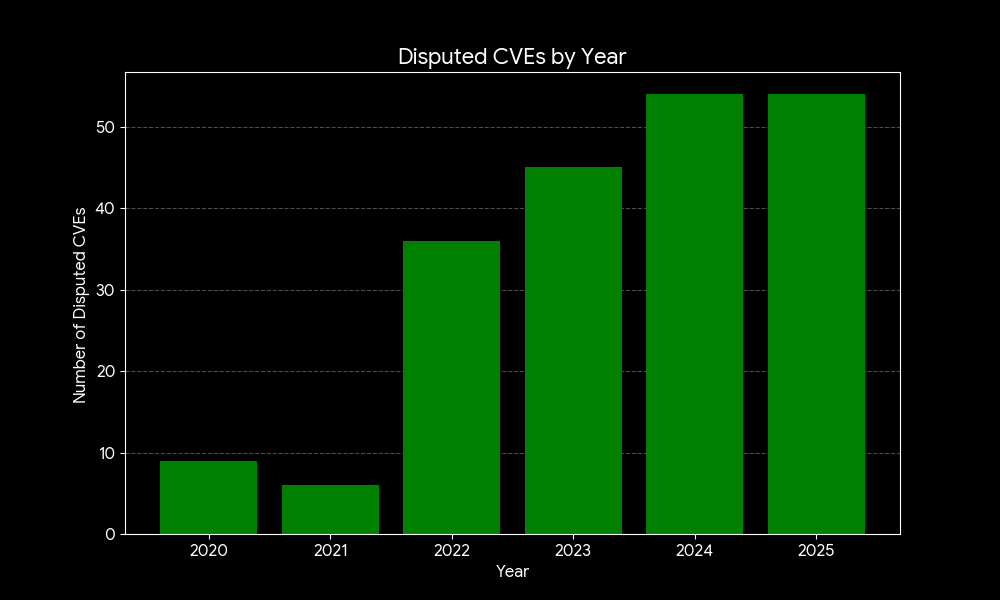

Now in 2026, things even got worse. The rise of generative AI has worsened the noise around CVE reporting by producing a surge of low-quality, technically incorrect submissions that waste maintainers’ time. In fact, the curl project recently ended its bug bounty program after being flooded with AI-slanted reports that appeared plausible at first but didn’t describe real security issues, leaving maintainers to shoulder an unsustainable review burden.

CVE-2023-42282: A Case to Debate

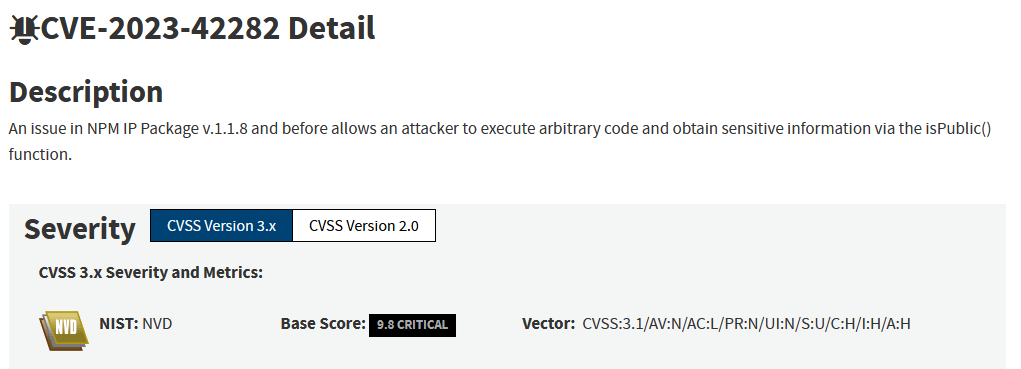

A notable example of this researchers/maintainers’ friction emerged when the critical severity CVE-2023-42282 was published against the popular `ip` npm package:

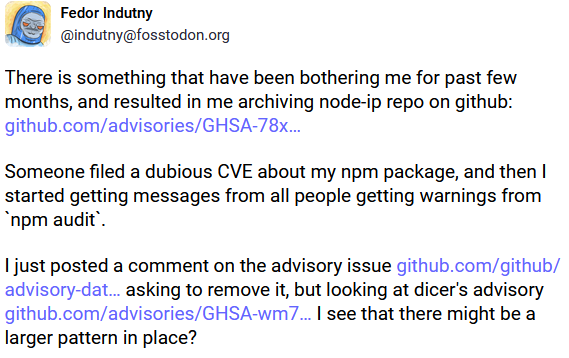

The researcher who reported and filed the CVE claimed that the library fails to properly verify whether an IP address is public, potentially leading to severe consequences. The maintainer’s reaction was direct: “I believe that the security impact of the bug is rather dubious.” He requested that the CVE be disputed, explaining that the chances of the vulnerable isPrivate() or isPublic() functions being called with user input were very low, since their purpose is simply to check whether an IP address is private or public, and because IP addresses would usually be provided by the OS, treating it as a critical issue was unjustified.

The maintainer went even further and archived their project because of this incident:

Cases like that, which create tension between maintainers and security researchers over how to assess real-world risk, bring up a bigger question in appsec: Who is really responsible for the safe use of an OSS library?

Researchers vs. Maintainers

On one side, researchers are scanning thousands of projects, sometimes responsibly trying to prevent hidden risks, but at other times the motivation for credit and recognition could make them publish nonviable security risks. The vulnerability reports they publish feed directly into CVE databases.

On the other side, maintainers often push back, arguing that severity is inflated or that the exploit assumes unrealistic control of input. Their stance: input validation is the developer’s job, not the library’s.

This tension becomes even sharper with libraries. A small utility function may be perfectly safe when used carefully, but dangerous if fed untrusted input. Should every library defend against every possible misuse? Or is it on developers to know the risks when they integrate it?

The Community Weighs In

The story of the ‘ip’ NPM package didn’t end with the maintainer’s rejection. In the GitHub advisory thread, community members confronted him directly, pointing out scenarios where the bug could cause real harm (discussion). Others shared real-world examples that would be exposed to attacks if left unpatched (example).

These responses show that while a maintainer might view a vulnerability as “theoretical”, downstream users sometimes experience the opposite, a practical, exploitable risk.

The CVE Disclosure Process

Another ingredient here is how CVE disclosure works. Researchers can register CVEs without the maintainer’s agreement. Once a CVE goes public, application security tools and SCA scanners pick it up. Suddenly, thousands of developers see a red “critical” flag in their dashboards. They ask for fixes, security teams escalate, and pressure lands on the maintainer, even if the maintainer disputes the issue.

This cycle puts enormous strain on open source maintainers, many of whom are volunteers. At the same time, it protects the ecosystem by making risks visible.

The Bigger Question

CVE-2023-42282 highlights the gray area between “this is a real security hole” and “this is just unsafe usage.” It forces us to ask hard questions:

- Should maintainers design libraries to be ‘idiot proof,’ or should developers bear full responsibility for validating inputs and understanding the risks?

- How do we balance transparency (through CVEs and disclosures) with fairness to maintainers who may not agree with the severity?

There’s no simple right or wrong here. But as the ecosystem grows more dependent on OSS, we need better conversations about responsibility and what “secure by default” really means.

What do you think? Who should carry the heavier responsibility: maintainers, or the developers who use their libraries?

For more information on how to protect your software supply chain from the latest vulnerabilities, check out the JFrog Platform by scheduling a demo, taking an online tour or starting a free trial at your convenience.